– Excerpt of an interview with the pioneer science museum professional

Jayanta Sthanapati

Sixty years ago, Syt Ghanshyam Das Birla, a philanthropist and an eminent industrialist of the Birla Family decided to donate their palatial building at Birla Park on Gurusaday Road in Calcutta for establishing an industrial museum by the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, Govt. of India. He was close to two of the towering personalities of that era – Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Prime Minister of India and Dr Bidhan Chandra Roy, Chief Minister of West Bengal. On 7th December 1954, Mr Birla expressing his desire sent a proposal, through Dr Roy, to Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, the then Union Education Minister and Vice-President of CSIR. The proposal was accepted, and approval was accorded by the Prime Minister. The property was transferred to CSIR in 1956.

A committee was constituted by CSIR, with Dr B.C. Roy as Chairman to specify the scope and manage finances of the industrial museum, which was subsequently named as Birla Industrial and Technological Museum. The committee took an important decision to appoint the adequate number of professionally qualified human resources who would not only contribute intellectually and technically to develop the museum, but also would be able to help sustain its growth and expansion. As the first step in this direction, Mr Amalendu Bose, who was working as Patent Inspector, after completing higher studies in Chemistry in Calcutta and the US, was appointed as Planning Officer of BITM in November 1956. Under his leadership, the BITM was made ready for inauguration by Prof Humayun Kabir, Union Education Minister on 2nd May 1959.

Mr A Bose was a visionary, who realised the importance of inducting right kind of people, having a passion for this profession, and between 1957 and 1963, he recruited some matured officials, experts in respective fields, like Mr P.M. Niyogi, Mr S. S. Ghosh, Mr R.C. Chandra and Mr C.S. Pai. He further recruited Mr S.K. Ghose, Mr R.M. Chakraborti and Mr S.K. Bagchi, three young engineers with many years to go, who would contribute towards the betterment of science museum for a longer period.

Mr Samar Kumar Bagchi had served the BITM as a Curator in different grades from 1962 to 1979 and after that as Director till 1991. The present interviewer, also a former Director of BITM, who worked under Mr Bagchi for more than thirteen years, talked to the octogenarian pioneer at his residence in Kolkata, on July 13, 2013, to trace the events that laid the foundation of science communication endeavours through science museums.

Jayanta Sthanapati: Sir, let us begin our conversation by asking you to please give me a brief account of your origin and family background?

Samar Bagchi: I was born in Purnea, in the State of Bihar in 1933. I am one of the six brothers and one sister. My father was a Health Officer under District Board at that time. He had a touring job. When I think I was just five or six years old, we went to Dumka, my father on transfer. Dumka is now in the state of Jharkhand. It was the District Headquarters of the Santhal Parganas at that time. Dumka was a marvellous place, and our house was situated just below the beautiful picturesque Hizla Hill. My father was transferred again from Dumka to Munger in Bihar. I did my matriculation from Munger. During that time my father expired, and we shifted to Calcutta.

Sthanapati: Please tell me about your college education and hobbies.

Bagchi: I joined Scottish Church College in Calcutta. I used to play football from the student days. It was a passion for me, and for that, a little bit of sacrifice in education was made. I also played badminton. Scottish Church at that time had marvellous teachers. I especially remember our science teacher Prof D.P. Ray Chaudhuri, whose physics book was also very famous. He used to come in the class with experiments. I have never forgotten the intricacies of Ohm's Law, the way he taught us with experiments in the classroom.

We had a great teacher in Bengali called Bipin Babu. In fact, Bipin Babu was responsible for a love of poetry reading. When he used to come in the class, and he took up a piece, he used to recite poems from English, from Bengali. A young boy at that time, coming from a small town, I never read any poetry. I was amazed to see his memory and the passion with which he used to read poetry. That has created perhaps a lasting impression, which later on made me a great lover of poetry, both English and Bengali. This is the way I grew up.

Sthanapati: What did you do after graduation?

Bagchi: After doing my B.Sc. from Scottish Church College, I joined School of Mines in Dhanbad in 1953. I was there for four years, and I graduated in 1957. At that time, after graduation, we didn't use to get any job in a mine. We had to appear in a stricter examination for 2nd Class and 1st Class Mine Manager's Certificate. After two years of training in a mine we had to appear for the 2nd Class Mine Manager's Certificate examination, then only I am eligible to work in a mine as a Manager. So I appeared, then got my 2nd class and I joined a colliery in the Magma Coalfield, situated between Dhanbad and Asansol. I worked there for two years and then I got the 1st Class Mine Manager's Certificate. I started working in a mine.

Sthanapati: Had your career in science museum happened by choice or by chance?

Bagchi: After serving in a mine for six months with a 1st Class Mine Manager’s certificate, I noticed an advertisement in the newspaper for the post of a Curator (Mining and Metallurgy) in Birla Industrial and Technological Museum in Calcutta. It came to my eyes suddenly. I didn't have any idea of a science museum. I didn't look for it also. When I saw the advertisement that a person is needed in Calcutta, I immediately applied. The reason why I wanted to leave coal mine is, during my college days at the School of Mines, while doing pole vault, most probably because of that I had a disc slip, and I had to be operated in 1959. Because of that underground work was becoming difficult for me. Although mining was a very lucrative job, I decided to apply for the job. The salary that I was offered in BITM was less than half the salary and the privileges that I was getting in the mines. There were not many candidates, and I got the job.

Photo 2. Mr Samar Bagchi, Curator of BITM in 1964

Sthanapati: Who were your prominent colleagues when you joined the BITM?

Bagchi: I joined the BITM in 1962, I think on 1st September. Mr Amalendu Bose was the Head of the Museum. He was an excellent administrator, a well-disciplined man, who never got excited, never got flustered. Dr Saroj Ghose, a doyen of science museum profession in India, was already there four years before. I also found Mr Rathindra Mohan Chakraborti, a classmate of Dr Ghose in Jadavpur University, as my colleague.

Sthanapati: Some of us in NCSM claim that BITM is the first major science museum in India. Do you agree with that?

Bagchi: Yes I do. BITM is the first major science museum in the country. Of course, there was a small science museum in National Physical Laboratory, New Delhi. Then there was a science museum also in Pilani. In Pilani museum, the emphasis is on the industry. Dr Bidhan Chandra Roy, Chief Minister of our state and the Chairman of our Executive Council was keen to see that BITM develops as a science museum, something like the Science Museum London or the Deutsch Museum, Munich.

Sthanapati: Did you interact with stalwarts like Mr G D Birla, Mr M P Birla, Dr B C Roy or Prof S N Bose in BITM?

Bagchi: Of course many prominent personalities used to come to our museum when I was there. But I did not meet Mr G D Birla in BITM. Mr M P Birla was the Chairman of our Finance Committee. He used to take a lot of interest in our work. Prof S N Bose had come once for a lecture during my time, most probably.

Dr B C Roy had expired before my joining the museum. But then B C Roy was so interested in the museum. I find the first Executive Committee minutes; there was a controversy between B C Roy and G D Birla. Mr Birla wanted the museum to be a copy of the Pilani museum where an exhibition of industrial objects will be there. B C Roy is mentioning, as noted in the minutes, that he wants an educational museum, not a museum of the showpiece of industrial objects. And the science museum in India has taken a note of what B C Roy said, science museums in India are really educational museums.

Sthanapati: I understand you had unearthed the history of the building where BITM is situated. Would you kindly share that story with us?

Dr B. C. Roy had asked the house of Birlas when they were planning to leave this building, where BITM is situated, that why don't you donate this building? They left the building because the family was becoming bigger. So they had to make different houses. This house was also quite old.

The present building was built up in 1923, and that has a history. It was also a discovery, you can say by me. It was known in Calcutta that this house belonged to Satyendra Nath Tagore. But that was not correct. This I didn't know. When the 25th Anniversary of Birla Museum was being celebrated, I planned to bring out a small brochure on the museum, on the history of the institution.

I met Satyendra Nath’s son; he was I think the second son. I brought him to the museum. When I was showing him around the museum, he told me “No, this part was not there. …. No, this room seems much bigger than what it was” and so on. He made a lot of statements which went against the belief that the present building belonged to Satyendra Nath. Then, I talked to Mr Amalendu Bose, who had retired from NCSM by that time. Mr Bose said that he had been to a party in which a very prominent member of the Birla family was there and he had told him that the building (S N Tagore's) was demolished and a new building came up. I had appointed a history person to go through the archives and find out the history. But all those information was not found by her. When I heard this from Mr Bose, I immediately made an appointment with the senior most Birla, Mr L. N. Birla. I went to his office and met him. He said, “Yes yes, that building was completely demolished from the foundation, and we built a new house and N.K. Guin was the architect.

I came back to my office, opened up the telephone directory and I found three or four Guins. I phoned up the first Guin, who I think was the son or grandson of N.K. Guin. They were still practising as architects or so. He said, “Yes, we have given the architectural design and the old building was demolished.” So then I went to the archive of the Calcutta Corporation. In Calcutta Corporation, the archive was wonderfully maintained. They brought out the whole file and showed me their old drawings. There was a pond there, where now the Modern High School is situated.

When Mihirendra Nath Tagore, son of Satyendra Nath Tagore was brought to my museum he was telling stories about the museum. He told that Rabindra Nath Tagore used to come here during Holi festival and all of us used to go and take a dip in the pond and come and sit here. He said Rabindranath used to take food on a lotus leaf. The place where I used to sit in the museum, just outside that there is a small place and I used to imagine that Tagore is sitting there and taking food in a lotus leaf.

That’s the real story of our museum building, in which we are situated. It was published in our Silver Jubilee Brochure in 1984.

Sthanapati: Which was the first significant gallery you developed in BITM?

Bagchi: When I joined, I had no experience in a science museum. Since I was the Curator of Mining and Metallurgy, Mr Bose asked me to plan out a Mining gallery. There were Copper; Iron & Steel gallery; and Petroleum galleries in BITM, at that time. I planned out a Mining gallery, which was opened in 1964.

Photo 3. Mr A.K. Sen, Union Minister of Law and Commerce, inaugurated Mining Gallery of BITM on 27 June 1964.

Photo 3. Mr A.K. Sen, Union Minister of Law and Commerce, inaugurated Mining Gallery of BITM on 27 June 1964.

Sthanapati: When did you develop the mock-up Coal Mine?

Bagchi: In 1978, a new museum building came up in the BITM campus. It was decided that there would be an underground coal mine in the basement of this building. I planned out the mock-up coal mine and it was opened for public viewing in 1983, where visitors used to get a real feeling of a coal mine. It was a great draw in BITM, which is true even now also. I can claim that in the whole world except the mining part of the Technika Museum in Prague, there is no other science museum, where some significant mining gallery is there. Chicago Museum of Science and Industry has a mining gallery, a coal mine, but nothing compared to our museum.

Sthanapati: Let us know about some important educational activities introduced during your time.

Bagchi: I started a project called ‘Animalorium’. That was, of course, the inspiration of the writer Mr Narayan Sanyal. He is a relative of mine. He had been to the USA to his daughter and there in a park, he saw loan service program of birds and other things. When I heard that it struck me. So I planned the Animalorium, where we had three pits, for snakes, for lizards and all that. I used to take up the non-venomous snakes. We used to hold live demonstrations with various types of lizards, some venomous and some non-venomous snakes. Of course, there was an incidence of the person who was looking after was bitten by a venomous snake, Russell Viper, and he was hospitalized. This was his bravery, he did not know how to handle it properly, but was trying to handle a venomous snake. I was terribly afraid at that time because the day he was struck, there was a press conference going on in my museum. I don't know what would have happened if they had heard it.

Photo 4. Smt. Sheila Kaul, Union Minister for Education and Culture, inaugurated Mock-up Coal Mine of BITM on 11 June 1983.

Photo 4. Smt. Sheila Kaul, Union Minister for Education and Culture, inaugurated Mock-up Coal Mine of BITM on 11 June 1983.

Then we started aviary where birds were kept. Then we have begun the aquarium and then hare corner. So these corners were started. Then we started a loan service program of pets, which became very successful. Hares were taken by the children, then fishes were taken by the children, birds were taken by the children. So this called Loan Service Program of Pets. Pet Club was a very popular activity.

I am sad that some parts have been closed down. Maybe that the snake pit was closed down because of the objection from animal lovers. But that kind of animal love is going on in India for dogs and all other creatures also. That’s good that we should have an understanding of the biodiversity, which is with us and without which we cannot live.

Photo 5. A live demonstration with a snake in BITM by Dipak Mitra.

Photo 5. A live demonstration with a snake in BITM by Dipak Mitra.

Sthanapati: What were other major educational programs introduced in BITM during your time?

Bagchi: BITM gets a mention in the Encyclopedia Britannica, as one of the outstanding museums, in the world for its educational programs. I may humbly claim, a little bit, which I had a small part to play in organizing those educational activities from the museum.

The mobile science exhibition was started in 1965. That was a very good idea of Saroj Ghose. We also had a big program of Science Demonstration Lecture, a series of lectures based on syllabus – say the Atom; Acid, Bases and Salts; say Electric generator; Electricity, then Properties of Liquids, and like that a series of perhaps 12 or 13 items which were developed by our education staff. Education Division was quite active at that time. Persons like Mr S K Mitra and others delivered more than a thousand lectures or so in West Bengal. They used to visit schools in small towns and villages along with demonstration units in a small van. This science demonstration lecture and mobile science exhibition made BITM known throughout Bengal. And throughout maybe even Eastern India, because we used to go at that time with the mobile science exhibition to Bihar, Assam, and also to Orissa. Then we started School Loan Service program. We used to make small boxes with demonstrations on the scientific principles that are there in the syllabus. Scientific kits were loaned to the schools, may be for seven or ten days. But carrying these things became a problem and later, of course, this program did not fully materialize. It went on for some time but later on it was hard to continue.

Photo 6. Science Demonstration Lecture delivered by Mr S.K. Mitrain BITM.

Photo 6. Science Demonstration Lecture delivered by Mr S.K. Mitrain BITM.

We had the Creative Ability Centre. I remember about Mr P M Neogi, our Curator, who was the inspiration for that. Then we had the HAM centre. Mr S Thirumurthy, a Curator, was a great enthusiast of HAM Centre and during that time HAM movement, training of HAM, everything started. Unfortunately, the activity was closed for various reasons.

So, HAM, Creative Ability Centre, Loan Service, Science Demonstration Lectures, different kinds of educational programs were started during that period, with which I was involved. Not only that I fostered these, but I used to take part myself.

Sthanapati: I understand at one stage you tried to engage volunteers for the demonstration of gallery exhibits. Why was it discontinued?

Bagchi: After seeing American Museums, I started Volunteer Guides at one time. I made an advertisement in the newspaper. A lot of people applied and they became volunteers, as it is done in America. It’s an honour for the volunteer to come and they do it so gladly. Here also a lot of people came. But you know that was very sad that the service given by the outsiders free of cost, was not properly treated by some of our staff. Due to this, they felt that they were unwanted. I used to treat them with great honour, but some employees disliked them and that actually antagonized quite a few.

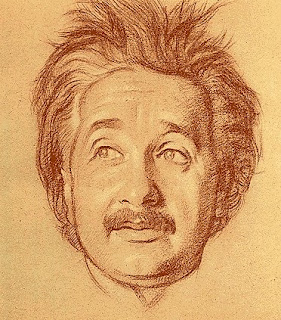

Sthanapati: In 1979, during the Birth Centenary of Albert Einstein, BITM exhibited an outstanding exhibition. What was your contribution, as a Director, in creating the Exhibition?

Bagchi: A significant educational activity that was continuously going on in BITM, displayed on life and works of scientists. Some such exhibitions used to come from USA, USSR, UK, Germany and other places. We also developed exhibitions on life and works of scientists, two exhibitions I should specially mention. One is the Life and Works of Three Scientists. We arranged an exhibition on Jagadis Chandra Bose, Prafulla Chandra Ray, and Satyendra Nath Bose. The three scientist exhibition was mainly photographic. The prize exhibition that we made was on Einstein's Centenary, I think was great. In that, of course, I should mention the help I got from two persons, one from Jadavpur University, Dr Tapen Roy, and the other was Dr Partho Ghosh when he was with the British Council. Dr Tapen Roy, who is now dead, helped us in creating many experiments for the exhibition.

I can claim that, whatever information I have, no such significant exhibition on Einstein with experiments have been done by anyone else in the world. I was the principal planner of this exhibition. Of course, other education staff, like Mr D K Pathak and others had helped us.

When I was reading the life of Einstein, I got information that in the house of the Royal Astronomer in Greenwich, I think his name is Dyson or so, a pride of place used to occupy a painting of Einstein drawn by English painter Sir William Rothenstein. I immediately wrote to Royal Observatory. They said this picture is not there, you write to such and such, and so on. Later on, the painting was discovered in a remote village in Scotland and the lady who owned it sent me its photograph. After the exhibition was over, the photograph occupied a pride of place in my room, at the back of my seat. I don't know if it is still there or not. That was a unique exhibition we did.

Photo 7. A Copy of the portrait of Prof Albert Einstein drawn by Sir William Rotenstein.

Photo 7. A Copy of the portrait of Prof Albert Einstein drawn by Sir William Rotenstein.

Sthanapati: BITM at one stage had patronised for science club movement in West Bengal. Why did you discontinue such support?

Bagchi: Science Club movement was a great thing during my time. The movement was already there. What BITM did was to foster science club movement. We arranged a separate competition for members of the science clubs in our annual event called Eastern India Science Fair. I remember you used to come to science fair, from Jadavpur side from a science club. We had a look upon you from Science Fair. We spotted you there. Both Dr Ghose and I thought that this gentleman must be brought to the science museum. So you came through science fair and science club.

When science club movement grew up all over West Bengal, then the need was felt for an Eastern India Science Club Association. It was formed, in which Deepak Dan of Gobardanga Renaissance Institute, Dr Dipankar Roy from Jadavpur University, they all took the lead to establish this. But I think now, of course, this movement is dead. Because Paschim Banga Vigyan Mancha has come in, PBVM has become an all Bengal organization. The science club movement has died out gradually.

Sthanapati: Has the visit to science museums abroad influenced your exhibit development work in India?

Bagchi: Yes, indeed, my tour to Exploratorium in the United States in the early 1980s. The centre has interactive science exhibits, not the history of science exhibits. We know that London Science Museum, Munich Museum, the Smithsonian Institution, all these show the historical objects. Dr Frank Oppenheimer built up the Exploratorium in San Francisco, a museum where the understanding of science came in.

I believe you have seen the film by Charlie Chaplin called 'Modern Times'. In the Modern Times, Charlie Chaplin shows that humans have been crushed by machines. It’s a black magic which has come. We don't know how a Television works. We don't know how a motor car works. The technology has come with which people do not have any understanding. It is like a black box.

So, Frank Oppenheimer thought that we must create an institution which will make people understand basic science. Frank Oppenheimer started the science centre in a different way called Exploratorium, where all exhibits are working exhibits, interactive exhibits. It’s not only one way where you push a button, something happens. It’s a two communication, where the exhibit also speaks to you.

While in San Francisco, I used to enter the Exploratorium with the janitor at 7 in the morning and used to come out when the museum was closed. I took extensive notes. When I came back, I made quite a few exhibits here based on my experience. After me, I think, Mr A K Date went there, and then you went and spent many days in studying those exhibits.

So, when the NCSM came in, the inspiration to build interactive exhibits in India was brought from two institutions, the Exploratorium, and the second is Ontario Science Center in Toronto. First is, of course, the Exploratorium.

Photo 8. An interactive exhibit of the Exploratorium in the late 1980s.

Photo 8. An interactive exhibit of the Exploratorium in the late 1980s.

At that time there was a great controversy in the world of science museums, whether to have hands-on exhibits also in historical science museums or not. But even London Science Museum had to open Launchpad where only interactive exhibits are there.

In India of course, it was not possible to have historical science museums, because we did not pass through those stages of historical developments of Industrial Revolution, which the Europeans and Americans had gone through. So, NCSM decided to set up Science Centers in the country mostly with hands-on exhibits like the Exploratorium.

Photo 9. An interactive exhibit of the Launchpad in the late 1980s.

Sthanapati: Perhaps the most popular science program of the 1980s was ‘Quest’ that you presented in the Indian National Television for many years. What is the story behind its creation?

Photo 9. An interactive exhibit of the Launchpad in the late 1980s.

Sthanapati: Perhaps the most popular science program of the 1980s was ‘Quest’ that you presented in the Indian National Television for many years. What is the story behind its creation?

Bagchi: Sometime in 1982 Dr Aloke Sen, Program Executive of Doordarshan Kendra Kolkata told me that he had been to Germany under an exchange program and there he saw an interactive science quiz program on television called 'Head to Head'. He showed me the video of the German program in Max Mueller Bhavan in Kolkata.

There were parents and their children as participants in the quiz program and two non-science persons used to present.

Aloke Sen was interested in producing a similar program but in a different format, for the national television channel. He intended to involve two Germans, who were to come to Calcutta in exchange, in the first episode of the program.

I said, “Yes, we can do”. So my colleagues like Mr S K Mitra and others planned out experiments. Then those two Germans came. They first went to see the studio, an old studio in Tollygunge. When they saw the studio, they said, “No. No, we are not going to appear in this”. So, Aloke Sen was in trouble. Then they came to my museum with Dr Sen. After seeing the experiments, and they got interested. They said, “This is OK”. The first Quest program was recorded with them. Then, of course, it became a regular program and conducted for five years from 1983 to 1988. I got National Award along with Dr Partha Ghosh.

You know, in the Quest program there are two groups – Einstein Team and the Bose Team. They are all from class XI and class XII from the good schools of Calcutta. We used to conduct the experiments, and they had to answer, what is going on. Only one minute was given to them to think and then come out with the answer. I was amazed at the answers that were given by the students.

For a major part of my program, Dr Partho Ghosh appeared with me. Then Partho Bandyopadhyay, who was in the museum as a museum assistant, he came for one year. Then we stopped it and then it was carried on in the name of Quest by two Professors from the Calcutta University for I think a year or so and then it was closed.

Sthanapati: In early 1980s BITM did a significant work for some backward tribes in Purulia. Would you please elaborate the work done there?

Bagchi: When the task force had recommended that the museum should be set up in three-tier – National level, four National museums in Calcutta, Bangalore, Bombay and Delhi, then the State museums and the District museums. It had said that the district museums should take part in the socio-economic development of the district. It should not be a copy of the national museum or so. It should not simply display exhibits. But it should take part in the socio-economic development of the district. I as Director of the museum took it seriously.

I had a great colleague, Mr Amalendu Roy, who was transferred from Bangalore to Purulia to head the District Science Centre, Purulia. He has expired. He had been collecting agricultural implements for the science museum in Bangalore, and he had some experience, perhaps from his childhood also about agriculture. He was a very practical man. When he brought those implements from South India, he started making similar implements there (at Purulia). So, Roy with a social activist there, who was a political worker also of a party, organized a training program for the Santhal tribals in the museum. The trainees took away the implements. Then hearing that such a training program has taken place, others came from the Kheria tribals. Kheria Shabars in Purulia is one of the poorest tribes of Bengal. Amalendu Roy became very popular in Purulia in a short time. He started training for the Kheria Shabars. We gifted them the implements that were made from our museum money.

We then went to Xavier Institute of Social Service in Ranchi. There we selected two persons and appointed them as Technical Assistants for our project. We bought motorcycles for them so that they could go from village to village to oversee the work. So, we started training the tribals in multi-cropping, mixed-cropping. They were only growing jowar, bajra and bhutta (corn). Then we started making dug wells, then ponds. So a tremendous work began in 45 villages.

I fostered such activity. I reported this in International Conference of Museums in Buenos Aires. I was the Key speaker there, and I showed as to how a tribal community was really helped by a museum in self-sustenance. Purulia museum, of course, took the lead in the matter of socioeconomic development of the district.

You see it was an excellent work. The Statesman published a full page report titled, “Ray of hope for the Kherias”. Mahasweta Devi wrote a big article on the work of the District Science Centre, Purulia in Economic and Political Weekly. A lot of important people who were doing such work, NGO bodies, very important people, used to come to Purulia to see the work.

It went on very well for a couple of years. But later on due to various reasons, we stopped this activity, during my time itself.

When we left the work then Mahasweta Debi, the writer, she was the President of the Kheria Shabar Samity. When we were doing work, not much was being done by her at that time. But then when we left, then she helped them very much.

It was a movement started by Purulia museum. I take pride in that Amalendu Roy had done a great job there. I remember him. Whenever I go to Purulia, I meet his daughter, who is there. She is a school teacher there, of a very important school.

Sthanapati: Your association with professionals outside NCSM.

Bagchi: The BITM I should say was extending the connection with the outside world. A lot of scientists, poets, dramatists, and others used to come. People used to come. I had ordered to my PA that even if a person from a village comes, without any shoes, he should be allowed to enter into my room and sit on the sofa. Even if I am in a meeting, and if it is not a confidential meeting, he should be made to sit in the room. I used to open the museum for outside organisations, environmental organisations, Himalayan trekkers and so on. They used to come and hold exhibitions. They used to come and hold seminars. Because of that, I being the Head of the museum, I was asked to be present. So hearing all those lectures etc. my mind also got changed. Environmental understanding that I have now mainly has come from BITM. I always tell in meetings that Birla Museum has made me what I am today.

Dr Tarak Mohan Das came to my museum and first made slides in my museum in the Television Studio. The recording was made on “Vanishing Forest”. I gave many lectures with those slides in different Rotaries, in Kolkata.

I used to go to the auditorium and take lectures. I have never taught in a school or so or a college, but then I feel that I have a knack for teaching, which I am carrying on till now.

When I retired, the person who used to look after me, my attendant, Sakur Khan, he used to come to my house and say “Sir, Abhi koi nahi ata (No outsider comes now).”

Sthanapati: The Festival of Science Exhibition of NCSM that travelled in the USA during 1985-1987 was developed primarily in the premises of BITM. What was your role in that mega event?

Bagchi: We took that great exhibition “India: A Festival of Science” to the United States in May 1985. It travelled in eight American Cities. I had gone at two places, Chicago and Charlotte. Besides giving full support from BITM for fabrication of exhibits, I was personally responsible for the development of some important sections of this exhibition.

That was a great experience also. I went to Orissa village, to find out a person who knew how to make tribal iron, ancient method of iron making. This was found out by someone else. When I got to know, myself and Mr R C Chandra, our Exhibition Officer went to that village, stayed there for three days, took photographs, made a pit, made a furnace and then we showed this in the exhibition.

So two things, you see, I was told by an anthropologist, late Prof Surajit Sinha, who was the Vice-Chancellor of the Vishwa Bharati University. He said once that if you ever make an exhibition, make a presentation on two things of India's contribution, one is music and the other is language. So, I made four panels each on music and linguistics, besides historical exhibits on ancient iron. I worked with a linguist of Calcutta University, Dr. Satya Ranjan Bandyopadhyay for many days. He was like a sage, a great scholar, with whom I worked. And then the music also. Indian classical music is very old. We went to a temple in North Calcutta, where South Indian Pandits chant the Vedas, in an original way. We tape recorded that. We also took sound recordings from the Vedic Institute in South Calcutta. We used to play the tapes in the section on music in the exhibition.

Sthanapati: I remember, one afternoon in June 1979, some of our staff along with a large group of outsiders gheraoed (besieged) you. Why did such staff unrest happen in BITM?

Bagchi: National Council of Science Museums was formed, in April 1978, I think. Before that, we were in CSIR. CSIR has got a big umbrella of Trade Union. Some of our staff thought that if NCSM comes up then they will lose this umbrella and their demands perhaps would not be met by the new organisation.

You know BITM at that time, and later on the NCSM, we were all non-corrupt. But then there was some staff; they would not go to Mobile Science Exhibition tours on one pretext or other. Some staff when they were sent to tour, without going to the tour, they sit in the home. This was all happening in 1978 and 1979. This was going on at that time when we had no union. But we decided that we will not submit to any unjust demand. A few members of BITM staff were suspended. As a result, one day some of our employees with the help of a large group of outsiders besieged me in my office until their demand was met, i.e. withdrawal of the suspension orders. Then the museum had to be closed for three months.

After the museum was opened, there was an agreement signed. The option was given to the staff, and thirty employees of BITM shifted to other laboratories of CSIR. But then BITM was entirely peaceful during my time, without any baton, without any punishment and there was no union. It ran very well. So for 12 years or so it was very peaceful. And after I retired, then also, and now also BITM is doing very fine. I think in every institution such situation may occur and it had taken place in my museum. I don't regret that this happened in my museum. We learnt a lot from this.

Sthanapati: Your advice to Curators and Education Officers who have many more years to serve the science museums in the country.

Bagchi: I think the museum is a dialogue with the society. Unless you understand the society, you cannot really work as a Curator or an Education Assistant. You should have a feeling for the people, to whom you serve. It’s not simply a job, it’s a mission, like a teacher, like a doctor, it has got a mission, mission to change the society. You need to have a mission to change the society through the science museum, so that they have a spirit of understanding science, as science and technology run today’s world. Our Curators should also study a lot. Go to the library. Such a wonderful library has been built in BITM, in West Bengal.

Sthanapati: Your premature retirement from NCSM.

Bagchi: Premature retirement from NCSM? Yes, enjoying life. Enjoy life with work. Nothing more should be said.

Sthanapati: What keeps you busy after retirement from BITM?

Bagchi: The Quest program gave me first-hand experience of work with hand. When I retired in 1991, my wish was to read poetry, or to see drama, or to see painting exhibition and all that. But then, I started taking workshops. More than 250 workshops have been taken all over India, from the Doon school to Slum school, from Kashmir to South India, from Gujarat to Arunachal Pradesh. I am moving around till now, taking workshops, at the age of 80 plus with eight operations in my body, including two spinal operations and I, am enjoying life.

Photo 10. Mr Samar Bagchi in an interactive session in JBNSTS, Kolkata.

Enjoying life at a time as William Shakespeare wrote in Hamlet, ‘The Time is out of joint.’ It’s figurative. But time is really very difficult. That’s the reason why it has made me a social and environmental activist. I write a lot on environment & development issues. I take camps on environment & development for the class eleven and twelve students, college and university students to make them understand the nature of the world in which we have to survive.

Photo 10. Mr Samar Bagchi in an interactive session in JBNSTS, Kolkata.

Enjoying life at a time as William Shakespeare wrote in Hamlet, ‘The Time is out of joint.’ It’s figurative. But time is really very difficult. That’s the reason why it has made me a social and environmental activist. I write a lot on environment & development issues. I take camps on environment & development for the class eleven and twelve students, college and university students to make them understand the nature of the world in which we have to survive.

The thought that pains my mind is 'What kind of world are we living behind'? Some scientists are predicting that human species will vanish from the earth within 100 years. So is this the world we are leaving behind?

Samar Bagchi: These are the good things, these are the exciting things that I did, I involved in with the others in the science museum in Calcutta.

During the Golden Jubilee Celebration of BITM in 2009, Dr Saroj Ghose, former Director of BITM and former Director General, NCSM wrote “I always wonder at the indomitable spirit of my colleague Samar Kumar Bagchi. He tied up the entire scientific and cultural community of Kolkata with the BITM during his tenure as its Director. And now he is tying up the larger community of science educators in the country in his campaign for the development of low-cost science teaching aids.”

The Interviewer: Dr Jayanta Sthanapati, former Director BITM, Director NCSM (Hqrs) and Deputy Director General NCSM had served the council for thirty-three years (1978-2011). He has recently completed his study on ‘History of Science Museums and Planetarium in India’, as a three-year (2013-2016) research project sponsored by the Indian National Commission for History of Science of the Indian National Science Academy, New Delhi.

Really wonderful. You have unearthed an untold history of BITM which will definitely helpful those who are interested in the field of "History of Science Museum".

ReplyDeletereghards

Very nice and informative interviews

ReplyDeleteThank you for this interview that shows how education in modern India was conceived.

ReplyDeleteWe know Shri Samar Bagchi as a great science educator, and are grateful to him for inspiring students in science and encouraging them to question, think, and explore.